But even with these guides, I find that I only delay the onset of debilitating writer's block. It's all fair and well to say "Batman angers Gotham's mobsters, compelling them to hire the Joker." It's an entirely different thing to explain how exactly he does that. If Batman doesn't actually do something, then our only device is to have a mob meeting in which gangsters say out loud "I'm angry at Batman. Let's hire the Joker." It's an even bigger sin in video games, because you're making the player feel like a side character in their own story.

Good storytelling demands that we show the protagonist (or a character) doing something. We have to get from angry mobsters to mobsters at the end of their rope.

So it's not just about going from "You = Rick" to "Need = the serum to turn him from a pickle to a human." We need action that drives a change in values. Beth takes the serum away, and suddenly Rick goes from being a happy pickle to an imperiled pickle.

There are models for this aspect of story. One is well-known for its champion, the great screenwriter Robert McKee. The other I only recently learned and has no name, so I'm going to call it The 27 Chambers, because kung fu movies and Wu-Tang Clan are awesome.

Both of these models are linear, because they're dealing with story in a connect-the-dots fashion. There's value in that paradigm because it keeps us from losing the audience in convoluted plot twists.

I'll tackle McKee's model first. It's more of a theory, but he applies it down to the level of individual lines of dialogue. If you haven't read his seminal work, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, go get it.

The theory is this: In any exchange or action, there must be a change. Characters must always be winning or losing, increasing or decreasing tension, or encountering or solving complications. A concise summary of this principle comes to three easy steps:

VALUE STATEMENT

CONFLICT

VALUE CHANGED

Here's a demonstration of how not to do it:

Son: Mom, get on the bus.

Mom: No!

Son: Mom, stop joking. Get on the bus.

Mom: I told you I'm not going!

Son: Stop being so stubborn!

We're all familiar with the sin of repeating beats. Beginning writers think that tension increases simply by demonstrating how stubborn Mom is. But as an audience, we take her at her word the first time. Meanwhile, we are burning the screentime clock. Somebody is paying money for this. We owe them better:

Son: Mom, get on the bus.

Mom: No!

Son: Mom, I'm not playing around, either get on the bus or--

Mom: You can't make me! You're not even my son! You're adopted!

Son: I already knew that. (Pulls out a rubber chicken) Now, are you gonna get on that bus or do I have to use this?

Now that hums a little more. And while a family secret and vulcanized poultry are shiny objects, they're just props. The underlying principle of changing values -- of revealing unexpected complications and potential danger -- is what compels us to throw rubber chickens.

Batman's stated value is to thwart crime in Gotham. The conflict? Their money-man is in Hong Kong. The change? Batman literally hunts a dude halfway around the world, upping the ante against the mob like never before.

Rick's stated value is survival. The conflict? He's knocked into a sewer filled with roaches and rats. The change? He upgrades his body and escapes... only to find himself in the lair of the Russian mafia.

You could almost think about each of these interactions as a "mini-story" within the larger meta-arc. Each interaction has a beginning, a middle, and an end. That's how the 27 Chambers model works.

I received this format from Jessica Bendinger, the writer of Bring it On and the podcast Mob Queens. It's beautiful in its simplicity. You start with your meta-arc. Your story has:

THE BEGINNING

THE MIDDLE

THE END

But you can break that down:

THE BEGINNING OF THE BEGINNING

THE MIDDLE OF THE BEGINNING

THE END OF THE BEGINNING

THE BEGINNING OF THE MIDDLE

THE MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE

THE END OF THE MIDDLE

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

THE MIDDLE OF THE END

THE END OF THE END

And then break it down again:

THE BEGINNING OF THE BEGINNING OF THE BEGINNING

THE MIDDLE OF THE BEGINNING OF THE BEGINNING

THE END OF THE BEGINNING OF THE BEGINNING

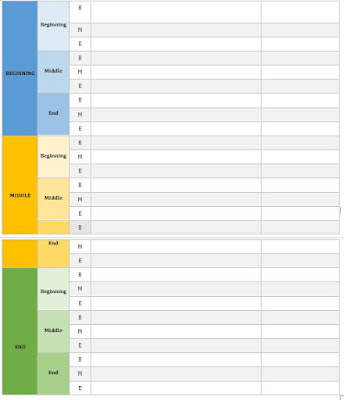

I won't beat the horse further. However, since learning this approach to story development, I completely abandoned any and all beat sheets and created a map of this using Microsoft Word. It looks like this:

This model provides you with the most direct, chronological method of writing your story. It also emphasizes a similar discipline as what McKee calls for. Each segment of the story -- even one as infinitesimal as the beginning of the beginning -- should have an end. Know what the cutoff is. Define it through action. Batman drops the Chinese banker off at GPD Headquarters. Beth takes the pickle cure serum and leaves Rick in the garage. The scene is over and what comes next will necessarily be based on or a response to what we just saw.

These models very much go hand-in-hand. One thing leads to another, and usually that also means that things will never be the same thereafter.

For my next trick, I'll attempt to reconcile the linear with the circular. Between five points of story, three acts, twelve steps in the hero's journey, seven components of a cat rescue, and 27 chambers, there's no common denominator. I think the key is a matter of proportion. The end of the end of the end doesn't need as much page space or screen time as the middle of the middle of the middle. With that in mind, I think the circular and linear can do a lot to inform each other and sharpen story development.

No comments:

Post a Comment