Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Continuing Toward the Grand Unified Theory of Story: A Couple of Linear Models

Thursday, January 20, 2022

Girl-Powered: A Narrative Review of Knights and Bikes

Wednesday, January 5, 2022

Reinventing the Wheel: An Integrated Model of Everybody's Story Circles

Which story structure do you like to use?

Story structure is an immensely important subject to study, because understanding structure enables you to bring it to your own stories. A story without structure is a kindergartner telling you about their trip to Disney World. The center cannot hold. All is sound and fury.

But asking "what structure do you use" isn't studying structure. It's asking Stan Lee who would win in a fight between Spider-Man and the Thing. There may be no such things as stupid questions, but "which structure is best" does not meet the criteria for a smart one.

I once offered in a class that it doesn't matter which one you use because they're all the same. I got a lot of blank looks. Then the instructor followed up with "they're all equally good and what you choose is a matter of preference, so find the one that works for you."

I don't agree with that. You can't take an English class and call yourself a linguist. You can't buy a hammer and call yourself a carpenter. You have to study the whole subject and make a practice of using all the tools. If you just use one story structure all the time and have no ability to use another type to either build or assess your stories, are you a storyteller or just someone that tells a certain kind of story?

I use multiple structures to build my stories. I think you can use them all at once. I do it frequently. I even used one I just learned four months ago to outline a western drama I'm writing. And while marveling at how well it worked in comparison to everything I thought about how I was subconsciously using it in the context of all the others. That got me to thinking about how I might have saved myself a couple of drafts if I'd been a little more conscious of that context. I went looking for a visual reference that would help me do that. Certainly, there was somebody out there who'd done it before, right?

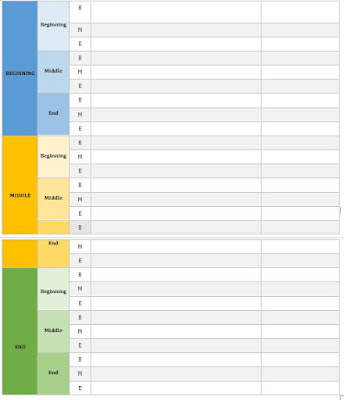

Not that I could find. So, I decided to make one. I found out why nobody had done it yet, because it wasn't easy. I wound up making a complete diagram of three well known models to get to the combined one. I'll share them here and a little background for anyone who's never encountered any of them.

And also because I insist on proving all those classmates who'll never see this that I'm right.

First and simplest Dan Harmon's Story Circle. And I mean "simplest" as a compliment. For all the modeling that the world's top storytelling scientists have performed, Dan has found elegance in simplicity. Eight, count 'em, eight major components. That's it. Eight episodes of Community and three episodes of Rick and Morty (on top of running both shows) can't be wrong. It works. Not only does it make brilliant TV, but he can explain it in less than four minutes on YouTube.

For those seeing this for the first time, there are some pros and cons. Pros first:

- Simple and streamlined. Identifies the big pieces of a story's requirements.

- Allows plenty of room to work out details.

- Loose enough to be adapted to most genres (horror is always different, right?)

- Small and simple. Could be used to plot multiple arcs and connect them into a larger narrative.

- Can lead to lots of ambiguity. How many beats between points? What are they?

- Allows you to misinterpret what individual elements mean, leading to plot holes.

- Leaves a LOT of work to be done in the actual writing.

- Much more specific and structured. Helps identify points between the most basic elements.

- The journey offers geographic orientation. It's a great way to connect events and locations.

- Forces you to get your characters out of bed and on the move.

- Helps connect plot points to avoid holes and disconnects.

- Strong temptation to chase rabbit holes like worldbuilding and tropes.

- Because of obstacles and enemies and magic, you could write a story in which the character doesn't do much and instead just has a bunch of stuff happen to them (Disney Princess Syndrome)

- Can lead to a misinterpretation that each story element gets an equal amount of page space or screen time.

- It's oriented to time/story space. If you have a defined word/page-count, it gives you a reasonably good estimate of what your allocations are for each portion of your story. It's great if you're writing for e-readers.

- Keeps you on pace throughout development.

- Establishes limits early so you don't plan more story than you can actually write.

- It's very open-ended as to actual things that must happen. This model is broad enough to work equally well for John Wick and Power of the Dog.

- Can cause you to feel like you're constricted by hard-and-fast rules. Hampers creativity.

- The terminology doesn't lend itself to nailing down plot points. What's the difference between debate and choice? When do you know you're out of one phase and into the next? It's not intuitive, so it could induce banging-head-against-wall syndrome from trying to sort it out.

- It's very character-focused. Between the first three elements and "Dark Night of the Soul," you could fall into the trap of writing 37% of your story inside your protagonist's head without them taking action.

- How do we keep from getting too far into our character's head or too far into White Walker land early in Act I? Simple. Let Harmon remind you that you must clearly define a NEED by the end of the Set-Up.

- What does Snyder mean by "fun and games" early in Act II? Campbell and Harmon have some ideas.

- Those synchronicity hiccups between Snyder and Harmon late in Act II? Campbell helps fill in the gaps.

- Want solid tension throughout Act II? Follow the sequence of Find the Treasure, Fight Bad Guys for Treasure, Face Death, and finally Take the Treasure.

- Is Act III lame? Is it just Frodo flying home on an eagle? Maybe he should reflect on how he almost threw the whole game. Don't let him master two worlds without seeking some atonement. All of that is essential action to demonstrate his change.

- Have some of these points make you feel like problems in your story are more easily solved? They should, because the unified model has enough overlap that you no longer feel constrained by Snyder's hard-and-fast percentages. They're guidelines upon other guidelines.

- We're also no longer grasping for ways to connect Harmon's eight elements. We don't have to talk to a guy with a portal gun or an 800-year-old Jedi, but there's now a space reserved for some sort of interaction or beat that can fulfill our story's needs.